Brahmi

According to Wikipedia:

Brahmi (/ˈbrɑːmi/ BRAH-mee; 𑀩𑁆𑀭𑀸𑀳𑁆𑀫𑀻; ISO: Brāhmī) is a writing system from ancient India[2] that appeared as a fully developed script in the 3rd century BCE. Its descendants, the Brahmic scripts, continue to be used today across South and Southeastern Asia.

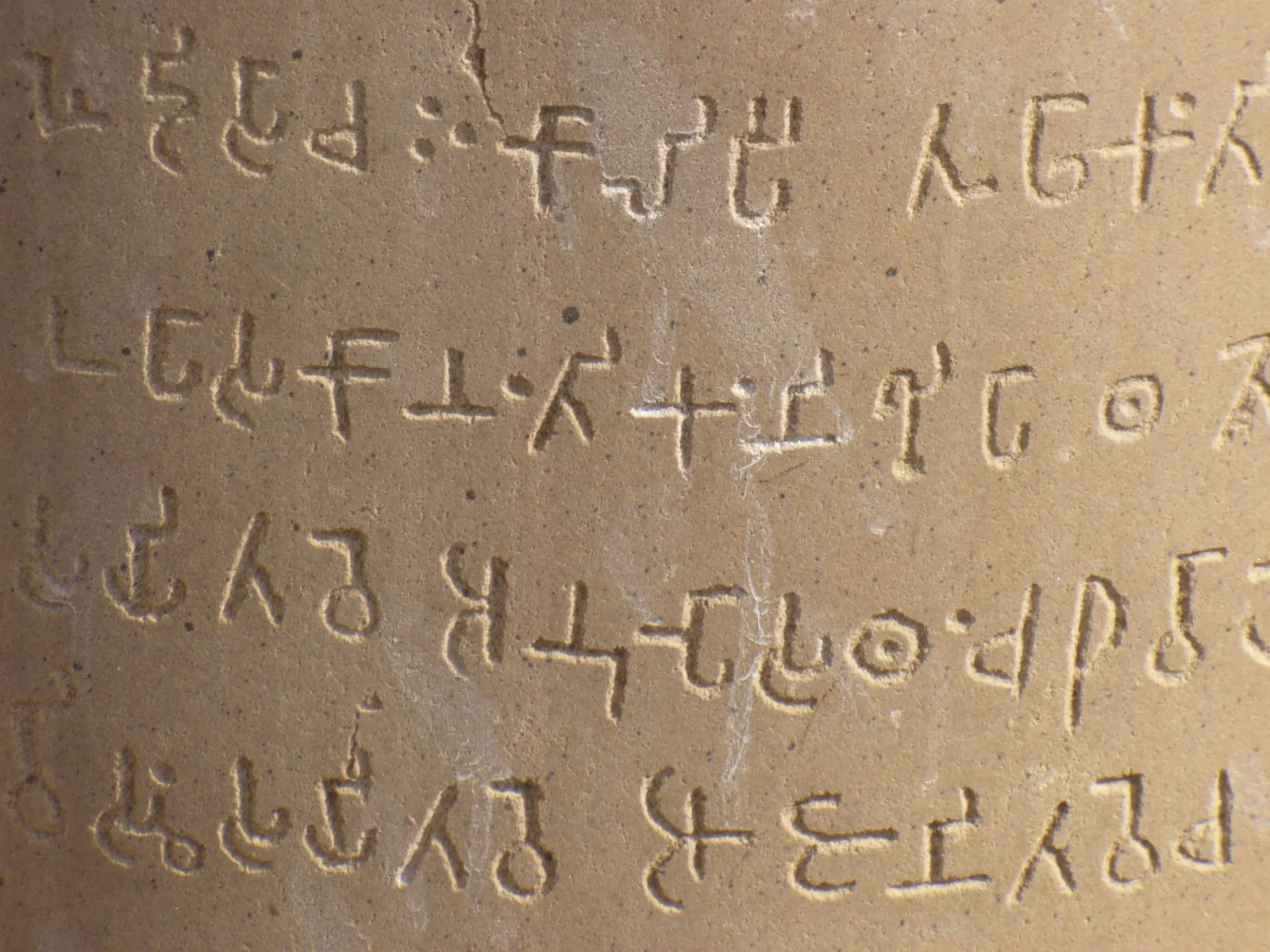

Brahmi is an abugida and uses a system of diacritical marks to associate vowels with consonant symbols. The writing system only went through relatively minor evolutionary changes from the Mauryan period (3rd century BCE) down to the early Gupta period (4th century CE), and it is thought that as late as the 4th century CE, a literate person could still read and understand Mauryan inscriptions. Sometime thereafter, the ability to read the original Brahmi script was lost. The earliest (indisputably dated) and best-known Brahmi inscriptions are the rock-cut edicts of Ashoka in north-central India, dating to 250–232 BCE.

Brahmi script on Ashoka Pillar in Sarnath (c. 250 BCE):

What is an abugida?

Section titled “What is an abugida?”Again, according to Wikipedia:

An abugida (/ˌɑːbuːˈɡiːdə, ˌæb-/ ⓘ;[1] from Geʽez: አቡጊዳ, ‘äbugīda) – sometimes also called alphasyllabary, neosyllabary, or pseudo-alphabet – is a segmental writing system in which consonant–vowel sequences are written as units; each unit is based on a consonant letter, and vowel notation is secondary, similar to a diacritical mark.

Characteristics

Section titled “Characteristics”Brahmi is usually written from left to right (although there is an example of a coin found in Eran which is inscribed with Brahmi written right to left).1

Brahmi is an abugida, meaning that each letter represents a consonant, while vowels are written with obligatory diacritics called mātrās in Sanskrit, except when the vowels begin a word. When no vowel is written, the vowel /a/ is understood.

Special conjunct consonants are used to write consonant clusters such as /pr/ or /rv/.

Vowels following a consonant are inherent or written by diacritics, but initial vowels have dedicated letters. There are three “primary” vowels in Ashokan Brahmi, which each occur in length-contrasted forms: /a/, /i/, /u/; long vowels are derived from the letters for short vowels. There are also four “secondary” vowels that do not have the long-short contrast, /e:/, /ai/, /o:/, /au/.

The collation order of Brahmi is believed to have been the same as most of its descendant scripts, one based on Shiksha, the traditional Vedic theory of Sanskrit phonology. This begins the list of characters with the initial vowels (starting with a), then lists a subset of the consonants in five phonetically related groups of five called vargas, and ends with four liquids, three sibilants, and a spirant.

In the early Brahmi period, the existence of punctuation marks is not very well shown. Each letter has been written independently with some occasional space between words and longer sections.

In the middle period, the system seems to be developing. The use of a dash and a curved horizontal line is found. A lotus (flower) mark seems to mark the end, and a circular mark appears to indicate the full stop. There seem to be varieties of full stop.

Baums identifies seven different punctuation marks needed for computer representation of Brahmi2

- single (𑁇) and double (𑁈) vertical bar (danda) – delimiting clauses and verses

- dot (𑁉), double dot (𑁊), and horizontal line (𑁋) – delimiting shorter textual units

- crescent (𑁌) and lotus (𑁍) – delimiting larger textual units

This website uses Noto Sans for displaying Brahmi characters.

𑁍

Footnotes

Section titled “Footnotes”-

Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3, pp. 27-28. ↩

-

Stefan Baums (2006). “Towards a computer encoding for Brahmi”. In Gail, A.J.; Mevissen, G.J.R.; Saloman, R. (eds.). Script and Image: Papers on Art and Epigraphy. New Delhi: Shri Jainendra Press. pp. 111–143. ↩